Care about food? Us too.

In the past couple of years, there have been a raft of policy conversations happening that will determine the future of the food system in Aotearoa New Zealand.

In 1826 French physician Anthelme Brillat-Savarin wrote: Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es: “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.” Our relationship with food is one of the most important we have. The way we cook and eat, the way we feed ourselves and the people around us, and where our food comes from provides a deep vision into our society and how it works.

Food reflects who we are, how we live, and the cultures that shape us. What we eat defines our health, our relationship with the environment, with the places we live, and the people we meet. It defines our future.

So these policy conversations, that have the potential to set our course for the next generation, are really important. And from where we're sitting they're a missed opportunity.

Animal Welfare Code of Welfare Proposals

I want to be clear that at Freedom Farms we whole-heartedly support of the ruling that farrowing crates for mother pigs should be transitioned out of use. Our position on that hasn't changed in 15 years, and it won't change in the future.

We work with a wonderful group of independently audited farmers who support their sows to give birth outdoors in maternity paddocks where they have their own straw-lined huts to build their nests and give birth. We love the work that our farmers do, and recognise the privilege it is to support their pork going to market.

But the way in which the farrowing crate ruling came about is an indictment on multiple governments and illustrates the lack of big picture thinking from the Ministry. Farm animal welfare is not a destination, or a box to be ticked, it's a journey of thousands of small steps – backed by a complicated mix of consumer demand, welfare science, economic imperatives and cultural shift. Good animal welfare policy can't happen via once-in-a-decade bun fights between the National Animal Welfare Advisory Committee and industry.

When New Zealand lead the world in 2015 by recognising animal sentience in our welfare policy, a conversation could have started about how farmers would be supported to transition in a safe, sustainable and economically viable way. Instead, the can was kicked down the road, and now farmers are facing a transition with 70% of the time they should have had behind them. You can argue coulda, shoulda, woulda all you like... what is happening now will see farmers exit the industry, endanger the welfare of the pigs who will be housed in systems that in many cases will need to be retrofitted and run by staff who have had less than ideal time to be trained, and ultimately result in NZ consumers being offered *more* pork raised in low welfare systems because of the increased reliance on imports.

Low Welfare Imports

At the moment well over half the pork we eat in New Zealand comes from overseas. Many of you have been on the phone to us since the new Country of Origin labelling came into effect in February asking why there is a list of 16 countries on the back of the bacon you used to buy (that you *thought* was farmed here) or what wording like 'raised in... but may not be processed in' actually means.

There are current 25 countries that New Zealand imports pork from... and there is dizzying variation in the welfare standards between all of them. Which is not to say all of them are bad... some are actually on a pathway to similar welfare standards to New Zealand. But raising welfare standards requires investment from the farmers, whether locally or overseas. And investment on farm means the price is going to go up at the grocery store. And we're currently in a global cost of living crunch, and for many people there is limited appetite for the food they buy costing more.

So what does all of this mean? It means without policy intervention that sets some baseline welfare standards for imported pork, there will be NZ companies that seek out low-welfare low-cost pork to import, and those products will drive down the price that local farmers can get. Which makes farming pigs in NZ less viable, which means more farmers will exit the market, which means more pork will be imported. We've watched this happen slowly over the past two decades, its just coming to a crunch point.

New Zealand isn't alone in these challenges. The exact same conversations are happening in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, the EU and some states in the US. There is progress happening – in the free trade agreements that NZ has signed (but not yet implemented) with the UK and EU, there is a whole chapter on animal welfare, that requires collaboration between the parties and prevents either party from reducing welfare standards to increase exports. The World Trade Organisation have also waded in with their (delightfully named) GATT Article XX(a) that permits countries implementing trade restricting policies to protect animal welfare values.

To be clear, this isn't about a ban on imported pork. There are only 100 pig farms in New Zealand selling pork commercially, if we completely turn off the imports tap, we simply don't grow enough pork to fill the gap. But we can be fair to the local pork producers AND be a good global citizen by using policy initiatives to drive progress forward for animal welfare, while bringing everyone with us.

The Environmental Stuff

The environmental implications of food production are extraordinary – and I could probably churn out a thesis on the complexity of them (don't worry, I won't).

There is policy working its way through the process that is designed to address New Zealand's greenhouse gas emissions (including pricing agricultural emissions) and make us 'world leaders' on climate change action.

We're not convinced.

I want to say this as plainly as possible: climate change is happening and it's affecting food production now.

Don't believe me? Just ask the Vietnamese rice farmers who have to plant their crops at night due to record-breaking heatwaves. Ask the Italian farmers who saw crop yeilds drop by 45% in the 2022 summer season due to a trifecta of drought, heatwaves and then heavy flooding in a period of just four months. Ask the grain farmers in China, India and South America and the USA who have experienced unprecedented agricultural disruption this year.

The carefully crafted response plan from NZ's biggest emitters of GHGs, the ruminant farming sector, has come in the form of He Waka Eke Noa. There is a huge amount of commentary on the proposals, the government's response and the pros and cons of the plan. We don't have anything to say that hasn't been said more eloquently elsewhere.

If you're interested in some balanced chat around the science, the latest episode of When the Facts Change with Bernard Hickey and guest Melanie Newfield is a good explainer.

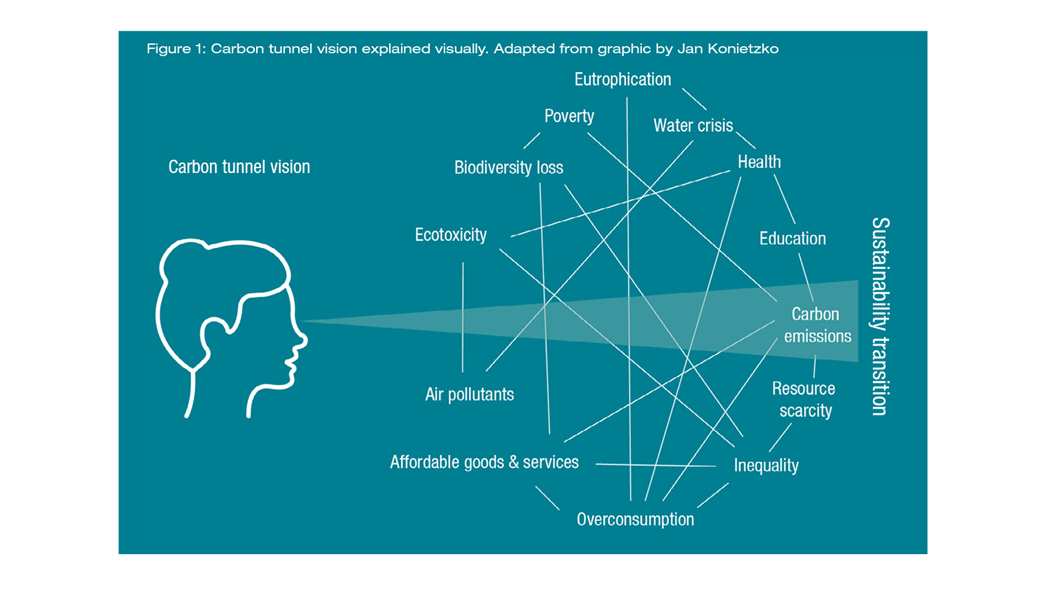

But our issue with a lot of this is that it feels like we're edging towards carbon tunnel vision.

Carbon tunnel vision is the simple idea that all our attention is getting soaked up with reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and we're missing an opportunity to address a lot of the other issues that also determine environmental reslience and agricultural sustainabilty. We're seeing this start to play out with claims of products being 'carbon neutral' without any transparency around what actions are being taken to achieve the right environmental outcomes.

We know internationally that some (very large) companies with very problematic track records on environmental choices are claiming to be net-zero, or edging towards it, simply by purchasing carbon credits to offset the emissions, without tangible reduction in their own footprint.

I'm going to write more about this down the track, but it would be a real shame to go all in on environmental policy that doesn't give us a sustainable system into the future.

The Big Picture

Which brings us to our final point: we need a plan.

It seems like this policy work is being hashed out, without a clear big picture plan (or any sort of systems thinking approach that considers how each part contributes to the whole). We have all the ingredients for something amazing – but the recipe isn't written yet.

There is a massive opportunity in front of us for New Zealand to develop a National Food Strategy that brings together all the pieces of policy to develop a framework to point us, producers and consumers alike, in a positive direction.

Its a bit weird that this hasn't happened yet.

Similar work has happened in the UK: in 2021, they published an independent review developed by a phenomenal group that included representatives from agriculture, industry, NGOs and lobby groups, academics and public health experts. The strategy set out four key pillars, with 14 recommendations.

1. Escape the junk food cycle and protect the NHS

2. Reduce diet-related inequality

3. Make the best use of our land

4. Create a long-term shift in our food culture

Embedded in the recommendations were animal welfare protections, environmental goalposts, trade policies, public health resourcing, protections for productive food-producing land, education initiatives both to help people make better food choices and to become food producers, reseach and innovation funding, and guidelines to improve transparency in food retail.

Their goals were simple:

- Make us well instead of sick.

- Be resilient enough to withstand global shocks.

- Help to restore nature and halt climate change so that we hand on a healthier planet to our children.

- Meet the standards the public expect, on health, environment, and animal welfare.

We want to see the same ambition for New Zealanders. We want someone to recognise that there is political capital to be found in making a plan for future generations of New Zealanders. One that doesn't prescribe what they eat, but gives them choices that are good for everyone.